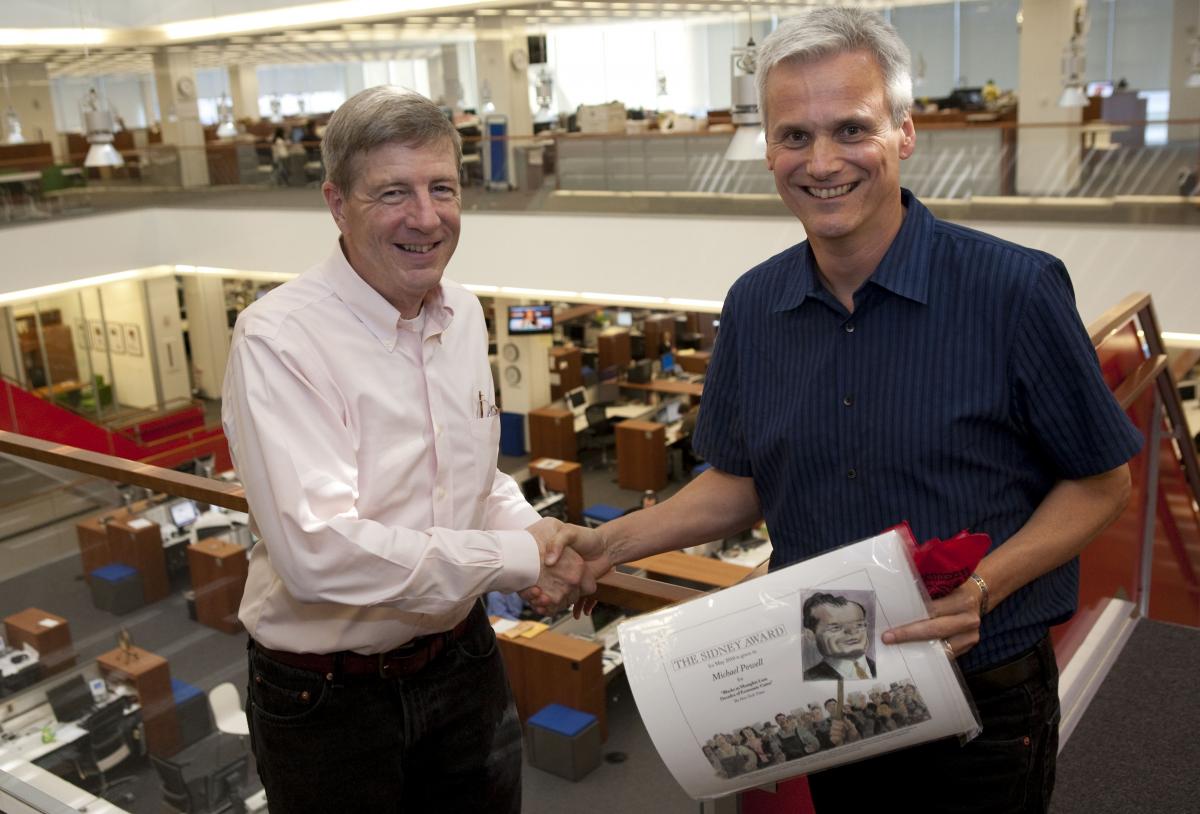

Michael Powell Wins May Sidney for New York Times Story on Income Inequality in Memphis’s African-American Community

NEW YORK: The Sidney Hillman Foundation announced today that Michael Powell has won the May Sidney award for the May 30, 2010 New York Times story “Blacks in Memphis Lose Decades of Economic Gains,” a striking portrait of the recession’s devastating effects on the black community of Memphis. The city’s woes are a microcosm of the ills affecting African-Americans across the country.

Powell’s findings include:

-

Rising unemployment and growing foreclosures in the recession have combined to deplete black wealth and income and erase two decades of slow progress.

-

Black unemployment in Memphis, mirroring national trends, has risen to 16.9 percent from 9 percent two years ago; it stands at 5.3 percent for whites.

-

The overall local foreclosure rate in Memphis is roughly twice the national average.

-

The City of Memphis and Shelby County sued Wells Fargo late last year, asserting that the bank’s foreclosure rate in predominantly black neighborhoods was nearly seven times that of its foreclosure rate in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Sidney Award judge Charles Kaiser said, “Powell has done a brilliant job of putting a human face on the wreckage caused by the most severe recession in America since the Great Depression. His severe indictment of American banking practices includes details of how black neighborhoods were targeted for the most expensive mortgages–even when their recipients qualified for cheaper ones, which would have brought the banks smaller profits.”

Powell has been a metro reporter for The New York Times since 2007. He was part of the team that won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News for its coverage of the sex scandal that led to resignation of Governor Eliot Spitzer. Last month, he switched beats to start covering economics. Before coming to the Times, Powell was a reporter for The Washington Post, where he wrote about everything from former Washington Mayor Marion Barry to voter fraud in Ohio. In 2000, he covered the presidential campaign for the Style section of the Post, and in 2001, he became the paper’s New York correspondent. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize three times. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife Evelyn and their two sons, Nick and Aidan.

Backstory

MAY, 2010

Michael Powell discusses his story about the effects of the recession on the African American community in Memphis.

1.Why did you decide to look into the effects of the recession on African American communities in Memphis?

A year ago, I wrote a piece with a colleague, Janet Roberts, on the foreclosure epidemic in New York City and its devastating effect on African Americans homeowners; banks have given blacks sub-prime loans at rates far greater than for white homeowners. Then I wrote of the City of Baltimore and its lawsuit against Wells Fargo, in which city officials charged that the bank’s discriminatory practices deepened Baltimore’s foreclosure problems.

The subject, race & foreclosure, came to haunt me. Given our nation’s terrible historical legacy with race, I was struck that we – policy makers in Washington, bank and mortgage officials and so on – had unleashed a whirlwind once more, to devastating effect.

I saw in Memphis a lens through which to examine this problem. Memphis now had an African American majority, and it was a place where blacks had made real economic strides in the past two decades, particularly in building wealth through their homes. That’s all gone now. The tale of that fall—and the role that banks played in it—had a power to it.

2. What surprised you as you did your research?

I had worked as a tenant organizer in a black and West Indian neighborhood in Brooklyn long ago, and so I was aware of the toll taken by block-busting, redlining and workaday discrimination. Still, the way in which the Great Recession has vaporized black wealth, the statistical totality of that destruction, surprised and frankly angered me. Because blacks came late to home ownership, much more of their wealth is wrapped up in their homes than for white families.

Beyond that, blacks in Memphis often were the first to get laid off, and often lacked retirement and health plans. It’s useful to be reminded that sometimes our ‘post-racial’ age is not quite so post-racial as we might like to imagine.

3. What has the response been since you published it?

I was surprised, frankly, by the depth and breadth of the response. I received dozens and dozens of emails, and the piece apparently sat atop the most-emailed list (our own Neilsen meter, God help us) for a few days. Some of the readers were angry and some blamed the homeowners, preferring to see a exclusive narrative of individual irresponsibility rather than systemic defrauding. But many more readers seemed genuinely moved, and a number of congressman promised to investigate this.

I’ll believe that when I see it.

4. Is there something you wish you had room to include in the piece but could not?

Oh, you always have themes you’d like to expand on, characters you’d love to flesh out. I would have liked to take a single homeowner and a single house and drilled down, walking a reader through the numbers and explaining how a hard-working, bright homeowner could sign mortgage papers that wound up destroying him. The process is not quite so mysterious as some readers suggested in their emails; rather few of us, I’d bet, read the fine print in that mound of closing papers. And I’d like to expand a bit on the role of the banks, Wells Fargo for sure, but also some of the other banks.

5. If you went back to this story in another year, what would you want to follow-up on?

I hope to get back there in the next six months. I’d like to follow a few homeowners, or former homeowners, as they attempt to rebuild their lives. And I’d like to follow that lawsuit.

The New York Times